By Tom Still

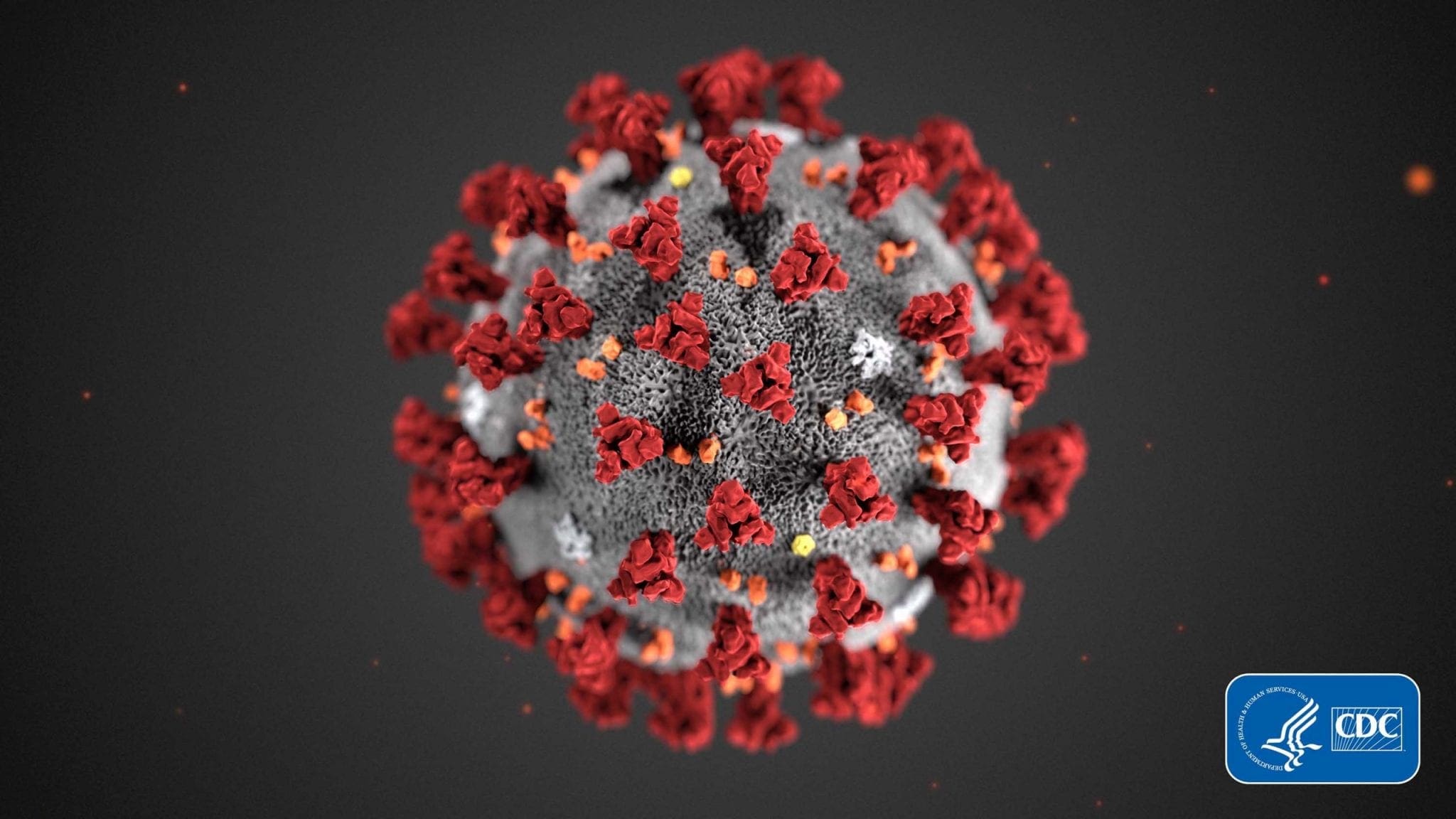

Image courtesy of CDC.

MADISON, Wis. – The scenario was eerily similar: A human respiratory disease of zoonotic origin, meaning it could be traced to animals, broke out in southern China and spread to 17 countries, eventually killing nearly 800 people.

It was called the SARS-Coronavirus and it was a major health worry from late 2002 until mid-2003. Two Wisconsin companies, Madison-based EraGen Biosciences and Waukesha’s Prodesse, were among the first in the world to produce a test for the SARS virus in 2003.

Neither company is around today, having been acquired by larger firms in the biotechnology space, but the same kind of scientific infrastructure that existed in Wisconsin when “severe acute respiratory syndrome,” or SARS, was making headlines is alive and well today.

With the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention predicting it’s only a matter of time before the current coronavirus reaches U.S. shores to some degree, there is some comfort in knowing that public and private scientists in Wisconsin are engaged in the effort to eventually thwart what is now called COVID-19.

A new test for the virus, which emerged in Wuhan, China, in late 2019, was developed by a Utah company using laboratory tools from Promega, the biotech firm headquartered in Fitchburg, Wis.

The test was developed with the help of Promega’s PCR Optimization Kit, and it’s different than a test developed in China when the outbreak began. It employs “polymerase chain reaction,” which is a method for copying samples from DNA millions of times to detect the presence of ribonucleic acid, or RNA.

The PCR kit is one of about 4,000 Promega products; the Utah company also worked with Promega in 2016 on a test for the Zika virus.

At the UW-Madison, scientists are working to build non-human primate models to test medical countermeasures such as vaccines and therapeutics. David O’Connor from the School of Medicine and Public Health and Thomas Friedrich from the School of Veterinary Medicine are a big part of that team, which is hoping to work with others around the world.

The UW-Madison researchers want to know how much of the virus makes its way into the body and bodily fluids; where in the lungs the virus infects; and how the immune system responds.

As Friedrich told Wisconsin Public Television: “The end goal is to understand how viruses evolve and the pathways they need to take to get from animals to humans and then become something that can be transmitted from one human to another. They have to overcome a lot of evolutionary barriers to do that and I think that the more examples we have of pathogens that do this, the better we can define what those barriers are and how they overcome them and then we can figure out hopefully how to stop this from happening.”

Yoshi Kawaoka, who holds dual appointments at the UW-Madison and the University of Tokyo, is also gearing up to help solve the research puzzle. Kawaoka has worked on finding answers to avian flu and the Ebola virus, creating an experimental vaccine that entered clinical trials in late 2019.

A company co-founded by Kawaoka, Madison-based FluGen, has begun clinical trials with its M2SR influenza vaccine in hopes of generating durable response to current and yet-to-come strains of the H3N2 virus family. It’s not a “universal vaccine,” as some might describe it, but it may be able to adapt to flu strains as they morph.

Here’s the sobering news: Don’t expect a COVID-19 vaccine to show up at your corner drug store any time soon.

Vaccines are notoriously hard to create, test and produce, usually taking years to develop. As the chief medical officer for the Wisconsin Department of Health Services said recently, “the ability to identify a target for a vaccine … sometimes takes decades.”

“Leadership of (the National Institutes of Health) has said that, optimistically, 18 months from now we might have studies showing an effective vaccine is available,” Dr. Ryan Westergaard told WisconsinEye. “The idea that we could have a vaccine for coronavirus after having just discovered it in nature six months ago is extraordinarily exciting.”

If the COVID-19 virus finds its way to Wisconsin, which it may not in a big way, the best defense against it will be isolation, testing and practicing good respiratory hygiene. Meanwhile, a lot of bright scientists here will be working on finding a more lasting solution.

Still is president of the Wisconsin Technology Council. He can be reached at tstill@wisconsintechnologycouncil.com.